What is cloud computing?

What is cloud computing, in simple terms?

Cloud computing is the delivery of on-demand computing services — from applications to storage and processing power — typically over the internet and on a pay-as-you-go basis.

How does cloud computing work?

Rather than owning their own computing infrastructure or data centers, companies can rent access to anything from applications to storage from a cloud service provider.

One benefit of using cloud computing services is that firms can avoid the upfront cost and complexity of owning and maintaining their own IT infrastructure, and instead simply pay for what they use, when they use it.

In turn, providers of cloud computing services can benefit from significant economies of scale by delivering the same services to a wide range of customers.

What cloud computing services are available?

Cloud computing services cover a vast range of options now, from the basics of storage, networking, and processing power through to natural language processing and artificial intelligence as well as standard office applications. Pretty much any service that doesn’t require you to be physically close to the computer hardware that you are using can now be delivered via the cloud.

What are examples of cloud computing?

Cloud computing underpins a vast number of services. That includes consumer services like Gmail or the cloud back-up of the photos on your smartphone, though to the services which allow large enterprises to host all their data and run all of their applications in the cloud. Netflix relies on cloud computing services to run its its video streaming service and its other business systems too, and have a number of other organisations.

Cloud computing is becoming the default option for many apps: software vendors are increasingly offering their applications as services over the internet rather than standalone products as they try to switch to a subscription model. However, there is a potential downside to cloud computing, in that it can also introduce new costs and new risks for companies using it.

Why is it called cloud computing?

A fundamental concept behind cloud computing is that the location of the service, and many of the details such as the hardware or operating system on which it is running, are largely irrelevant to the user. It’s with this in mind that the metaphor of the cloud was borrowed from old telecoms network schematics, in which the public telephone network (and later the internet) was often represented as a cloud to denote that the just didn’t matter — it was just a cloud of stuff. This is an over-simplification of course; for many customers location of their services and data remains a key issue.

What is the history of cloud computing?

Cloud computing as a term has been around since the early 2000s, but the concept of computing-as-a-service has been around for much, much longer — as far back as the 1960s, when computer bureaus would allow companies to rent time on a mainframe, rather than have to buy one themselves.

These ‘time-sharing’ services were largely overtaken by the rise of the PC which made owning a computer much more affordable, and then in turn by the rise of corporate data centers where companies would store vast amounts of data.

But the concept of renting access to computing power has resurfaced again and again — in the application service providers, utility computing, and grid computing of the late 1990s and early 2000s. This was followed by cloud computing, which really took hold with the emergence of software as a service and hyperscale cloud computing providers such as Amazon Web Services.

How important is the cloud?

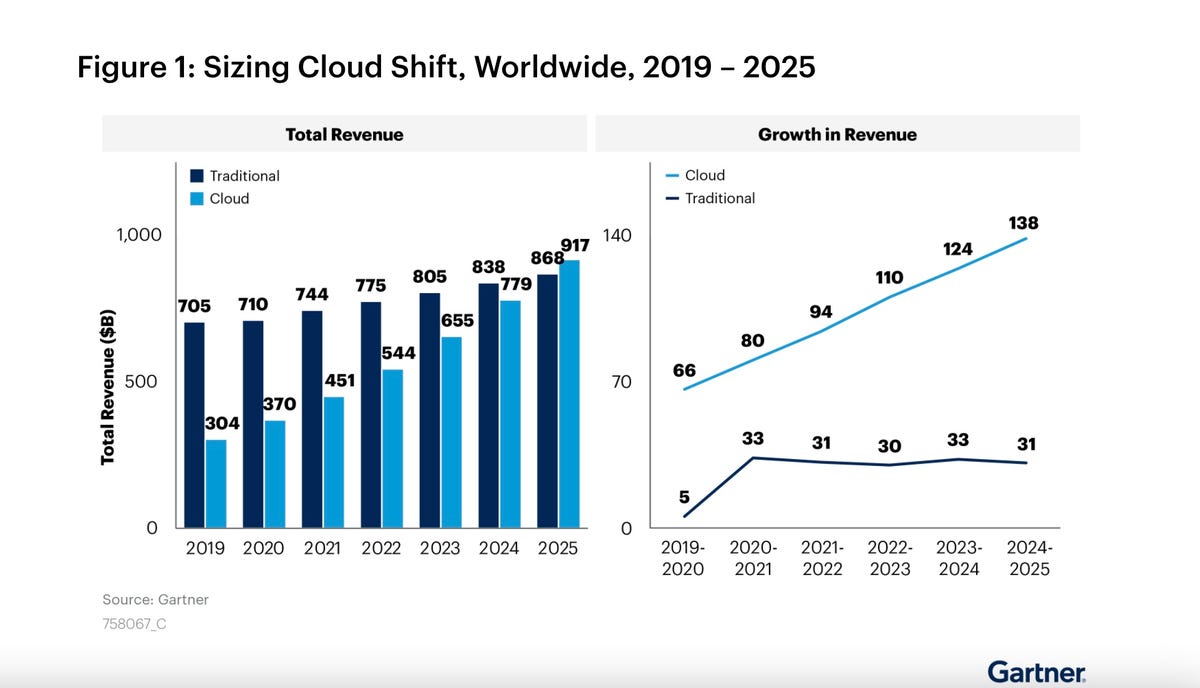

Building the infrastructure to support cloud computing now accounts for more than a third of all IT spending worldwide, according to research from IDC. Meanwhile spending on traditional, in-house IT continues to slide as computing workloads continue to move to the cloud, whether that is public cloud services offered by vendors or private clouds built by enterprises themselves.

451 Research predicts that around one-third of enterprise IT spending will be on hosting and cloud services this year “indicating a growing reliance on external sources of infrastructure, application, management and security services”. Analyst Gartner predicts that half of global enterprises using the cloud now will have gone all-in on it by 2021.

According to Gartner, global spending on cloud services will reach $260bn this year up from $219.6bn. It’s also growing at a faster rate than the analysts expected. But it’s not entirely clear how much of that demand is coming from businesses that actually want to move to the cloud and how much is being created by vendors who now only offer cloud versions of their products (often because they are keen to move to away from selling one-off licences to selling potentially more lucrative and predictable cloud subscriptions).

Predictions for cloud computing revenues to 2021 from 451 Research.

What is Infrastructure-as-a-Service?

Cloud computing can be broken down into three cloud computing models. Infrastructure-as-a-Service (IaaS) refers to the fundamental building blocks of computing that can be rented: physical or virtual servers, storage and networking. This is attractive to companies that want to build applications from the very ground up and want to control nearly all the elements themselves, but it does require firms to have the technical skills to be able to orchestrate services at that level. Research by Oracle found that two thirds of IaaS users said using online infrastructure makes it easier to innovate, had cut their time to deploy new applications and services and had significantly cut on-going maintenance costs. However, half said IaaS isn’t secure enough for most critical data.

What is Platform-as-a-Service?

Platform-as-a-Service (PaaS) is the next layer up — as well as the underlying storage, networking, and virtual servers this will also include the tools and software that developers need to build applications on top of: that could include middleware, database management, operating systems, and development tools.

What is Software-as-a-Service?

Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) is the delivery of applications-as-a-service, probably the version of cloud computing that most people are used to on a day-to-day basis. The underlying hardware and operating system is irrelevant to the end user, who will access the service via a web browser or app; it is often bought on a per-seat or per-user basis.

According to researchers IDC SaaS is — and will remain — the dominant cloud computing model in the medium term, accounting for two-thirds of all public cloud spending in 2017, which will only drop slightly to just under 60% in 2021. SaaS spending is made up of applications and system infrastructure software, and IDC said that spending will be dominated by applications purchases, which will make up more than half of all public cloud spending through 2019. Customer relationship management (CRM) applications and enterprise resource management (ERM) applications will account for more than 60% of all cloud applications spending through to 2021. The variety of applications delivered via SaaS is huge, from CRM such as Salesforce through to Microsoft’s Office 365.

Cloud computing benefits

The exact benefits will vary according to the type of cloud service being used but, fundamentally, using cloud services means companies not having to buy or maintain their own computing infrastructure.

No more buying servers, updating applications or operating systems, or decommissioning and disposing of hardware or software when it is out of date, as it is all taken care of by the supplier. For commodity applications, such as email, it can make sense to switch to a cloud provider, rather than rely on in-house skills. A company that specializes in running and securing these services is likely to have better skills and more experienced staff than a small business could afford to hire, so cloud services may be able to deliver a more secure and efficient service to end users.

Using cloud services means companies can move faster on projects and test out concepts without lengthy procurement and big upfront costs, because firms only pay for the resources they consume. This concept of business agility is often mentioned by cloud advocates as a key benefit. The ability to spin up new services without the time and effort associated with traditional IT procurement should mean that is easier to get going with new applications faster. And if a new application turns out to be a wildly popular the elastic nature of the cloud means it is easier to scale it up fast.

For a company with an application that has big peaks in usage, for example that is only used at a particular time of the week or year, it may make financial sense to have it hosted in the cloud, rather than have dedicated hardware and software laying idle for much of the time. Moving to a cloud hosted application for services like email or CRM could remove a burden on internal IT staff, and if such applications don’t generate much competitive advantage, there will be little other impact. Moving to a services model also moves spending from capex to opex, which may be useful for some companies.

Cloud computing advantages and disadvantages

Cloud computing is not necessarily cheaper than other forms of computing, just as renting is not always cheaper than buying in the long term. If an application has a regular and predictable requirement for computing services it may be more economical to provide that service in-house.

Some companies may be reluctant to host sensitive data in a service that is also used by rivals. Moving to a SaaS application may also mean you are using the same applications as a rival, which may make it hard to create any competitive advantage if that application is core to your business.

While it may be easy to start using a new cloud application, migrating existing data or apps to the cloud may be much more complicated and expensive. And it seems there is now something of a shortage in cloud skills with staff with DevOps and multi-cloud monitoring and management knowledge in particularly short supply.

In one recent report a significant proportion of experienced cloud users said that they thought upfront migration costs ultimately outweigh the long-term savings created by IaaS.

And of course, you can only access your applications if you have an internet connection.

What is cloud computing adoption doing to IT budgets?

Cloud computing tends to shift spending from capital expenditure (CapEx) to operating expenditure (OpEx) as companies buy computing as a service rather than in the form of physical servers. This may allow companies to avoid large increases in IT spending which would traditionally be seen with new projects; using the cloud to make room in the budget may be easier than going to the CFO and looking for more money.

Of course, this doesn’t mean that cloud computing is always or necessarily cheaper that keeping applications in house; for applications with a predictable and stable demand for computing power may be cheaper (from a processing power point of view at least) to keep in-house.

How do you build a business case for cloud computing?

To build a business case for moving systems to the cloud you first need to understand what your existing infrastructure actually costs. There’s a lot to factor in: obvious things like the cost of running a data centers, and extras such as leased lines. The cost of physical hardware — servers and details of specifications like CPUs, cores and RAM, plus the cost of storage. You’ll also need to calculate the cost of applications — whether you plan to dump them, re-hosting them in the cloud unchanged, completely rebuilding them for the cloud or buying an entirely new SaaS package each option will have different cost implications. The cloud business case also needs to include people costs (often second only to the infrastructure costs) and more nebulous concepts like the benefit of being able to provide new services faster. Any cloud business case should also factor in the potential downsides, including the risk of being locked into one vendor for your tech infrastructure.

Cloud computing adoption

It’s hard to get figures on how companies are adopting cloud services although the market is clearly growing rapidly. One set of research suggests that around 12% of businesses consider themselves to be ‘cloud-first’ organisations, and about a third run some kind of workloads in the cloud — while a quarter of firms insist they will never move on-demand.

However, it may be that figures on adoption of cloud depend on who you talk to inside an organisation. Not all cloud spending will be driven centrally by the CIO: cloud services are relatively easy to sign up for, so business managers can start using them, and pay out of their own budget, without needing to inform the IT department. This can enable businesses to move faster but also can create security risks if the use of apps is not managed.

Adoption will also vary by application: cloud-based email — is much easier to adopt than a new finance system for example. Research by Spiceworks suggests that companies are planning to invest in cloud-based communications and collaboration tools and back-up and disaster recovery, but are less likely to be investing in supply chain management.

What about cloud computing security?

Certainly many companies remain concerned about the security of cloud services, although breaches of security are rare. How secure you consider cloud computing to be will largely depend on how secure your existing systems are. In-house systems managed by a team with many other things to worry about are likely to be more leaky than systems monitored by a cloud provider’s engineers dedicated to protecting that infrastructure.

However, concerns do remain about security, especially for companies moving their data between many cloud services, which has leading to growth in cloud security tools, which monitor data moving to and from the cloud and between cloud platforms. These tools can identify fraudulent use of data in the cloud, unauthorised downloads, and malware. The country of origin of cloud services is also worrying some organisations.

What is public cloud?

Public cloud is the classic cloud computing model, where users can access a large pool of computing power over the internet (whether that is IaaS, PaaS, or SaaS). One of the significant benefits here is the ability to rapidly scale a service. The cloud computing suppliers have vast amounts of computing power, which they share out between a large number of customers — the ‘multi-tenant’ architecture. Their huge scale means they have enough spare capacity that they can easily cope if any particular customer needs more resources, which is why it is often used for less-sensitive applications that demand a varying amount of resources.

What is private cloud?

Private cloud allows organizations to benefit from the some of the advantages of public cloud — but without the concerns about relinquishing control over data and services, because it is tucked away behind the corporate firewall. Companies can control exactly where their data is being held and can build the infrastructure in a way they want — largely for IaaS or PaaS projects — to give developers access to a pool of computing power that scales on-demand without putting security at risk. However, that additional security comes at a cost, as few companies will have the scale of AWS, Microsoft or Google, which means they will not be able to create the same economies of scale. Still, for companies that require additional security, private cloud may be a useful stepping stone, helping them to understand cloud services or rebuild internal applications for the cloud, before shifting them into the public cloud.

What is hybrid cloud?

Hybrid cloud is perhaps where everyone is in reality: a bit of this, a bit of that. Some data in the public cloud, some projects in private cloud, multiple vendors and different levels of cloud usage. According to research by TechRepublic, the main reasons for choosing hybrid cloud include disaster recovery planning and the desire to avoid hardware costs when expanding their existing data center.

Cloud computing migration costs

For start-ups who plan to run all their systems in the cloud getting started is pretty simple. But the majority of companies it is not so simple: with existing applications and data they need to work out which systems are best left running as they, and which to start moving them to cloud infrastructure. This is a potentially risky and expensive move, and migrating to the cloud could cost companies more if they underestimate the scale of such projects.

A survey of 500 businesses that were early cloud adopters found that the need to rewrite applications to optimise them for the cloud was one of the biggest costs, especially if the apps were complex or customised. A third of those surveyed said cited high fees for passing data between systems as a challenge in moving their mission-critical applications.

Beyond this the majority also remained worried about the performance of critical apps and one in three cited this as a reason for not moving some critical applications.

Is geography irrelevant when it comes to cloud computing?

Actually it turns out that is where the cloud really does matter; indeed geopolitics is forcing significant changes on cloud computing user and vendors. Firstly, there is the issue of latency: if the application is coming from a data center on the other side of the planet, or on the other side of a congested network, then you may find it sluggish compared to a local connection. That’s the latency problem.

Secondly, there is the issue of data sovereignty. Many companies — particularly in Europe — have to worry about where their data is being processed and stored. European companies are worried that, for example, if their customer data is being stored in data centers in the US or (owned by US companies) it could be accessed by US law enforcement. As a result the big cloud vendors have been building out a regional data center network so that organizations can keep their data in their own region.

In Germany, Microsoft has gone one step further, offering its Azure cloud services from two data centers, which have been set up to make it much harder for US authorities — and others — to demand access to the customer data stored there. The customer data in the data centers is under the control of an independent German company which acts as a “data trustee”, and Microsoft cannot access data at the sites without the permission of customers or the data trustee. Expect to see cloud vendors opening more data centers around the world to cater to customers with requirements to keep data in specific locations.

And regulation of cloud computing varies widely elsewhere across the world: for example AWS recently sold a chunk of its cloud infrastructure in China to its local partner because of China’s strict tech regulations. Since then AWS has opened a second China (Ningxia) Region, operated by Ningxia Western Cloud Data Technology.

Consultants Accenture have warned that ‘digital fragmentation‘ is the result as different countries enact legislation to protect privacy and improve cyber security. While the aims of the laws is laudable, the impact is to raise costs for businesses. Three quarters of the 400 CIOs and CTOs surveyed expect to exit a geographic market, delay their market-entry plans or abandon market-entry plans in the next three years as a result of increased barriers to globalization.

More than half of the business leaders surveyed believe that the increasing barriers to globalization will compromise their ability to: use or provide cloud-based services (cited by 54% of respondents, versus 14% that disagree); use or provide data and analytics services across national markets (54% versus 15% ); and operate effectively across different national IT standards (58% versus 18%).

Over half said these increasing barriers will force their companies to rethink their: global IT architectures (cited by 60%) physical IT location strategy (52%); cybersecurity strategy and capabilities (51%); relationship with local and global IT suppliers (50%); and geographic strategy for IT talent (50%).

What is a cloud computing region? What is a cloud computing availability zone?

Cloud computing services are operated from giant datacenters around the world. AWS divides this up by ‘regions’ and ‘availability zones’. Each AWS region is a separate geographic area, like EU (London) or US West (Oregon), which AWS then further subdivides into what it calls availability zones (AZs). An AZ is composed of one or more datacenters that are far enough apart that in theory a single disaster won’t take both offline, but close enough together for business continuity applications that require rapid failover. Each AZ has multiple internet connections and power connections to multiple grids: AWS has over 50 AZs.

Google uses a similar model, dividing its cloud computing resources into regions which are then subdivided into zones, which include one or more datacenters from which customers can run their services. It currently has 15 regions made up of 44 zones: Google recommends customers deploy applications across multiple zones and regions to help protect against unexpected failures.

Microsoft Azure divides its resources slightly differently. It offers regions which it describes as is a “set of datacentres deployed within a latency-defined perimeter and connected through a dedicated regional low-latency network”. It also offers ‘geographies’ typically containing two or more regions, that can be used by customers with specific data-residency and compliance needs “to keep their data and apps close”. It also offers availability zones made up of one or more data centres equipped with independent power, cooling and networking.

Cloud computing and power usage

Those data centers are also sucking up a huge amount of power: for example Microsoft recently struck a deal with GE to buy all of the output from its new 37-megawatt wind farm in Ireland for the next 15 years in order to power its cloud data centers. Ireland said it now expects data centers to account for 15% of total energy demand by 2026, up from less than two percent back in 2015.

Which are the big cloud computing companies?

When it comes to IaaS and PaaS there are really only a few giant cloud providers. Leading the way is Amazon Web Services, and then the following pack of Microsoft’s Azure, Google, IBM, and Alibaba. While the following pack might be growing fast, their combined revenues are still less than those of AWS, according to data from the Synergy Research Group.

Analysts 451 Research said that for many companies the strategy will be to use AWS and one other cloud provider, a policy they describe as AWS + 1. These big players will dominate the delivery of cloud services: Gartner said two thirds of the spending on cloud computing services will go through the top 10 public cloud providers through to 2021.

Google Cloud Platform (GCP) (which also offers office productivity tools) is somewhere between the two. IBM and Oracle’s cloud businesses are also made up of a combination of Saas and more infrastructure based offerings.

There are vast numbers of companies who have are offering applications through the cloud using a SaaS model. Salesforce is probably the best known of these.

AWS, Google Cloud Platform and Microsoft Azure — what is the difference?

The cloud giants have different strengths. While AWS and Microsoft’s commercial cloud businesses are about the same size, Microsoft includes Office 365 in its figures. IBM, Oracle, Google and Alibaba all have sizeable cloud businesses too.

Increasingly the major cloud computing vendors are attempting to differentiate according to the services that they offer, especially if they can’t compete with AWS and Microsoft in terms of scale. Google for example is promoting its expertise around artificial intelligence; Alibaba wants to attract customers who are interested in learning from its retail know-how. In a world where most companies will use at least one cloud provider and usually many more, IBM wants to position itself as the company that can manage all these multiple clouds. Meanwhile AWS is pitching itself as the platform for builders, which is its new take on developers.

Cloud computing price wars

The cost of some cloud computing services — particularly virtual machines — has been falling steadily thanks to continued competition between these big players. There is some evidence that the price cuts may spread to other services like storage and databases, as cloud vendors want to win the big workloads that are moving out of enterprise datacenters and into the cloud. That’s likely to be good news for customers and prices could still fall further, as there remains a hefty margin in even the most commodity areas of cloud infrastructure services, like provision of virtual machines.

What is the future of cloud computing?

Cloud computing is still at a relatively early stage of adoption, despite its long history. Many companies are still considering which apps to move and when. However, usage is only likely to climb as organisations get more comfortable with the idea of their data being somewhere other than a server in the basement. We’re still relatively early into cloud adoption — some estimates suggest that only 10% of the workloads that could be move have actually been transferred across. Those are the easy ones where the economics are hard for CIOs to argue with.

For the rest of the enterprise computing portfolio the economics of moving to the cloud may be less clear cut. As a result cloud computing vendors are increasingly pushing cloud computing as an agent of digital transformation instead of focusing simply on cost. Moving to the cloud can help companies rethink business processes and accelerate business change, goes the argument, by helping to break down data and organisational silos. Some companies that need to boost momentum around their digital transformation programmes may find this argument appealing; others may find enthusiasm for the cloud waning as the costs of making the switch add up.

Cloud computing case studies

Cloud computing is gobbling up more of the services that power businesses. But, some have privacy, security, and regulatory demands that preclude the public cloud. For enterprises using cloud services with IoT, it’s critical to adhere to as many security practices as possible. Experts weigh in on the best approaches to take.